Module 2: Parameter Estimation and Model Fitting

Contents

Module 2: Parameter Estimation and Model Fitting#

In the previous chapter we introduced the basics of probability and hopefully convinced you that a probabilistic view of the world might be a useful framework in which to perform experiments and analyses. However, the critical reader may have noted that we didn’t really gain much in the way of tools that let us learn new things. We covered probability distributions and the Central Limit Theorem (CLT), but you would be justified in feeling that you don’t know how to use this new information practically. In this chapter, we will introduce the first two tools that a quantitative researcher should employ when attacking a data set:

Estimating model parameters from data and creating bounds on where we expect the parameter to exist.

Least-squares regression for fitting (linear) models.

Students who have seen the words “confidence intervals” and “linear regression” may be surprised that we’re spending time on these topics, but what we hope to show you is that these two tools are much more profound and useful than one might expect. In particular, we will see how these methods will help us start to answer the question “What do your data say?”

It’s also worth noting that these concepts form the basis of almost all advanced methods in statistics and machine learning, including dimensionality reduction, manifold learning, and clustering. The effort you put in to understand the basics of parameter estimation will help you use these tools more confidently and be more critical about when and how they are applied.

The atom of parameter estimation#

In this first section we’re going to discuss what it even means to “estimate a parameter”. In the previous chapter, we learned how to calculate moments and percentiles, but we didn’t discuss how to answer the question “what number should I tell my neighbor that I measured?” That is, if I have to report one value for some quantity, what value should I give? This is called making a point estimate of this quantity.

Parameter estimation questions

Once we’ve gotten our point estimate, some natural questions are:

How likely am I to observe this estimate?

How confident are you in this estimate?

How much deviation from this estimate should I expect if I re-did your experiment?

These questions are innately tied to a probabilistic and distributional way of thinking and can be answered by looking at the shapes of specific distributions. Specifically, we’ll show how to calculate classical confidence intervals, Bayesian credible intervals, and how to use bootstrapping to reconstruct how our quantity of interest is distributed. In particular, by the end of this module, you should see that bootstrapping is one of the most useful data analysis tools we have for attacking data of any kind!

Parameter estimation#

Before we can get to the exciting parts about intervals and curve-fitting, it is worth spending a moment being precise about what we are even talking about when we say “estimate this quantity.” To explore this, consider a set of \(N\) independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables \(x_i\). Let’s say that we’re interested in the mean of these random variables, which we’ll call \(\mu\). (For example, maybe we’re counting the number of heads in some coin flips, or the number of photons that hit a detector, or we want the mean time that a bacteria spins counter-clockwise.)

Let’s say that you’ve collected your data, the \(x_i\), and then your collaborator comes by and asks for your estimate of the mean, let’s denote it \(\hat{\mu}\); what do you say? You may be inclined to say that your estimate is simply the average (\(\bar{x} = \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}x_i\)), so you pull out a calculator and tell your collaborator that \(\hat{\mu} = \bar{x} = 10\). This works great until a week later you realize that you forgot to enter some of the \(x_i\) into your calculator and actually \(\bar{x} = 9\). You run over to your collaborator who kindly re-runs their analysis with \(\bar{x} = 9,\) but you are left wondering what the true mean, \(\mu\), of your random variables is. That is, if you added a few more observations, how much would the mean change? What if you repeated the experiment, what mean would you calculate then? If you had infinite data, what would you calculate?

Concerned by this, you take some time and repeat your experiment to get a new set of \(N\) observations, \(x_j\). You calculate \(\bar{x}\) and get 12! You’ve now seen \(\bar{x} = 9, 10,\) and 12, so which should you use for \(\hat{\mu}\)?

To answer this question, consider that we can treat not only our data \(x_i\) to be random variables, but also our estimate for the mean, \(\hat{\mu}\), to be a random variable. That is, we can try and describe our quantities, \(x_i\) and \(\hat{\mu}\) via probability distributions, \(P_x(X=x_i)\) and \(P_{\hat{\mu}(M = \hat{\mu})}\). However, the problem arises in that while we might have many (\(N\)) data points, \(x_i\), so that we can at least empirically describe \(P_x\), we only have one value for \(\hat{\mu}=\bar{x}\), so we can’t make a good description of \(P_{\hat{\mu}}\) empirically. Of course, if we could pin down \(P_{\hat{\mu}}\), theoretically or empirically, then all of the work in the previous section would help us immensely: we could calculate the expected value of \(\hat{\mu}\) and we could start to talk about the spread in \(\hat{\mu}\) that we might see.

The Big Problem

The problem of describing \(P_{\hat{\mu}}\) is what is called the problem of parameter estimation.

Going forward, we are going to continue trying to estimate the mean, \(\mu\), of a set of random variables, \(x_i\), but it’s worth noting that this problem generalizes to any parameter, \(\theta\), that might depend on our data. That is, while we’re going to elaborate on some specific calculations for \(\hat{\mu}\), we’re also going to outline the general techniques for any parameter estimator \(\hat{\theta}\).

Maximum likelihood and maximum A Posteriori estimates#

Before we get too much further, it should be said that there is no “correct” answer to the problem of “how should I calculate \(\hat{\theta}\), an estimate of \(\theta\)?” The Wikipedia page on point estimation lists nine different methods for answering this question, each of which uses its own assumptions and tools. What we want to highlight and emphasize are two of the most widely-used and intuitive methods, Maximum Likelihood Estimation (ML Estimation or MLE) and Maximum a Posteriori Estimation (MAP Estimation).

Maximum Likelihood Estimation#

The premise of ML estimation is simple: write down the likelihood function, \(f(x_i|\theta)\), and say that \(\hat{\theta}\) is the value of the parameter \(\theta\) that maximizes the likelihood. \(\hat{\theta}\) is known as the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) for the parameter \(\theta\). In the case of a mean of i.i.d. random variables, thanks to the Central Limit Theorem (CLT) we know that \(\mu\) is distributed as a Gaussian distribution with mean \(\mu\) and standard deviation \(\sigma = \sigma_x/\sqrt{N}\), where \(\sigma_x\) is the standard deviation of \(x_i\). If this isn’t clear, make sure to return to the previous set of notes for more details. The important point here is that the CLT tells us that sums are distributed normally.

Then ML estimation says that what we want to do is consider the likelihood of observing our data \(\bar{x}\) given different values for \(\mu\) and maximize it. The formula for a Gaussian distribution is

where \(z\) is the quantity that is distributed, \(\mu\) is the mean of \(z\), and \(\sigma^2\) is the variance of \(z\).\

Try It Yourself!

In Python, create a variable for the mean and variance, mu = 2 and sigmaSq = 1. Create a grid of \(z\)-values (maybe using np.linspace) and implement this formula to calculate the probability as a function of \(z\). Use plt.scatter to show the calculated probabilities versus the \(z\)-values and confirm that you see the expected “bell” curve!

In the present case, we are considering the distribution of the mean, \(\bar{x}\), so we will substitute \(\bar{x}\) for \(z\) in this equation. We then want to find the value of \(\mu\) that maximizes \(P(\bar{x}|\mu, \sigma^2)\), which we write in symbols like this:

This notation says that we should set \(\hat{\mu}\) to be the value of \(\mu\) (as indicated by the \(\mu\) under the \(\max\)) that maximizes the quantity in the square brackets. We can then take the logarithm of the stuff inside the brackets and drop the \(1/\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}\), as this won’t change where the function is maximized.

We can then quickly see that \((\bar{x}-\mu)^2\) is always positive, so this function is maximized when \(\bar{x} = \mu\) and we can write that the MLE is

because setting \(\hat{\mu}\) to this value maximizes the likelihood of observing the data \(x_i\).

If the math here is giving you difficulties, don’t worry; it’s here for the sake of being thorough, not because it’s essential to doing parameter estimation. The thing you should take away is that one way of making estimates is to maximize a likelihood function. Also, as the “Try It Yourself” boxes will try to point out, if you don’t understand a formula or equation on paper, you can always try and see it in your computer with Python.

Try It Yourself!

Again using mu = 2 and sigmaSq = 1, plot the quantity from Equation (15) \(\hat{\mu} = -\frac{(z - \mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}\) versus \(z\) alongside your bell curve from above. Where is this quantity maximized? Is it at the same place as the Gaussian distribution? Does changing \(\sigma^2\) affect anything?

In general, given some model connecting \(x_i\) and your parameter \(\theta\), which we’ll call \(f(x_i|\theta)\), then we can make an MLE, \(\hat{\theta},\) by maximizing this function over \(\theta\). In this case, it turns out that our gut call of using \(\hat{\mu} = \bar{x}\) was equivalent to using the maximum-likelihood estimator; this will not always be the case!

We’ll continue to make MLEs later, but for now we’ll summarize the idea as so:

Maximum Likelihood Estimation

Using a likelihood function \(f(\vec{x*|\theta)\), the Maximum Likelihood Estimator (MLE) \(\hat{\theta}\) is defined as \(\hat{\theta}\):

We’ll show in a moment that we can also make an MLE for the variance, \(\sigma^2\), of the distribution of the mean, \(\bar{x}\). If you’re uncomfortable with calculus, please feel free to skip over the following example to the formula at the end. What you should take away from this example and the one above is that ML estimation is often an exercise in algebraic manipulation: you take your likelihood and find where it is maximized. Once you have the formula, you’re good to go. However, we caution that if you can’t follow or assess the derivation, then you should be skeptical that you understand the formula well enough to use it on its own, and you should bolster your conclusions by making the estimate in a different way as well.

Example: estimating the standard deviation of a normal random variable#

First, for this estimate, we’re going to start by assuming that our data, \(x_i\), are distributed normally, with mean, \(\mu\), and standard deviation \(\sigma_x\). Then the likelihood of observing a specific point, \(x_i\), is given by subsituting \(x_i=z\) into Equation (13). We furthermore assume all of our observations are independent so that the likelihood of all the points is the product of their individual likelihoods. That is:

where \(\prod\) is the notation for a product of terms that increment \(i\) from 1 to N and the product of exponentials sum in the exponent.

We want to find the value of \(\sigma_x\) that maximizes this function, so we’re going to use a bit of calculus to do so (this problem isn’t as obvious as finding the estimate for \(\mu\)). First, however, we’ll again use the fact that maximizing the logarithm of the likelihood (often called the log-likelihood) is the same as maximizing the likelihood itself. This lets us write

Taking the derivative with respect to \(\sigma\) and setting it equal to zero lets us find the maxima of this quantity so that we can write

Now, we’re not quite done yet! This is an estimate for the standard deviation of the data. We said that we wanted an estimate for the standard deviation of the mean of the data (since it’s a random variable). However, if you try to do what we just did with the likelihood of the mean in Equation (14), you will encounter

but if we don’t know \(\mu\) (which we often don’t!), then using our best guess that \(\hat{\mu} = \bar{x}\) tells us that \(\hat{\sigma}^2 = 0\)! This is obviously incorrect, so to get even somewhere close to an answer, we had to assume that the data were normally-distributed.

So now we’ve found that our best estimate for the standard deviation of normally-distributed random variables is given in Equation (16). Note this formula takes the form we’d expect: it’s the definition of how we were taught to calculate the standard deviation! (Of course, this is a biased estimator of the standard deviation, but we’ll leave that discussion to other resources.) To get an estimate for the standard deviation of the mean, we’ll invoke the CLT, which tells us that the mean’s variance is \(\sigma_x^2/N\) so that we can use

as our estimate.

Again, the point of this example was not to prove that we can do math but to demonstrate what ML Estimation looks like in practice. There’s nothing particularly profound about it, but the formulas you learn are sometimes more constrained by algebra than whether they are really what you want to estimate. That is: You can sometimes maximize the likelihood function to estimate parameters.

Of course, if we’re not concerned with doing any algebraic analysis of the MLE, then we can always use computational techniques to find the maximum of our likelihood function. In the examples shown in these notes, where we only have a few parameters, this is probably doable, but in more complicated scenarios can be quite difficult. In this way, while ML estimation is a hugely successful methodology for estimating parameters, as you saw above and will see in the assignments, actually determining closed form answers for an estimator sometimes be tricky. In particular, for those not fluent in probability notation and calculus, bringing the simple premise of “maximize this function” to life can be quite difficult! As a result, statistics textbooks become complex lists of recipes, because it takes so much work to derive the results that it can’t be asked of the average user.

Thankfully, as we noted, there are alternative approaches that are sometimes more effective or practical. In the next section we’ll introduce Maximum a Posteriori Estimation (MAP Estimation), which still relies on mathematical theory to work, but in a more flexible manner, and later we’ll introduce the computational technique of bootstrapping.

Maximum a posteriori estimation#

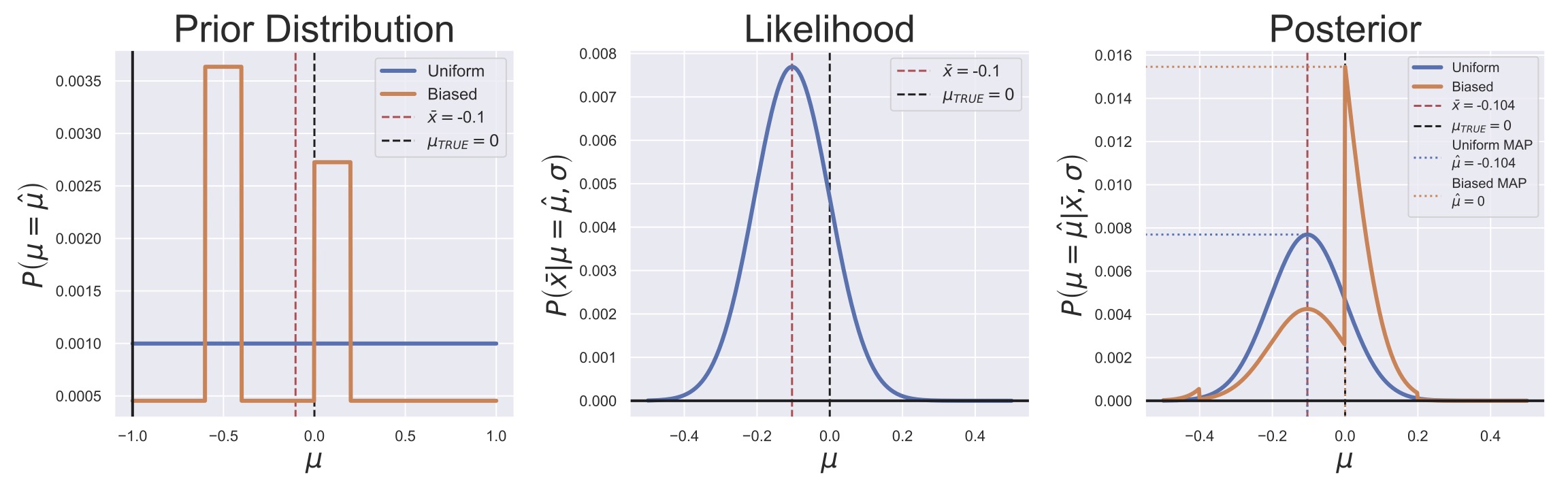

MAP estimation is a method for generating point estimates in a manner similar to MLE except that instead of maximizing the likelihood function, we find the maximum of the posterior distribution for our parameter (hence the name maximum a posteriori). Consider Fig. 16, where the Bayesian posterior generation process for the mean of some data has been illustrated.

In this Figure, we’ve posed two priors: a uniform prior for the mean, \(\mu\), from -1 to 1 and a Gaussian prior with a shifted mean and widened variance.

If we use the MLE for the standard deviation, the likelihood function for the mean is the same as in Equation (14):

We can then multiply these distributions to get the posterior computationally.

![Illustration of the MAP estimation of the mean of $N=100$ normally distributed random variables under two different priors. All three panels show the location of the MLE ($\hat{\mu} = \bar{x} = -0.104$) and the true population mean, $\mu_{TRUE} = 0.$ The left panel shows two different prior distributions for the sample mean, $\mu$. The center panel shows the likelihood function for the data ($\sigma$ was set to be $\sqrt{\text{Var}[x]/N}$). The right panel shows the two posteriors and their MAP estimates.](../../_images/Bayes_MAP_Estimates_Chapter2_Example.jpg)

Fig. 16 Illustration of the MAP estimation of the mean of \(N=100\) normally distributed random variables under two different priors. All three panels show the location of the MLE (\(\hat{\mu} = \bar{x} = -0.104\)) and the true population mean, \(\mu_{TRUE} = 0.\) The left panel shows two different prior distributions for the sample mean, \(\mu\). The center panel shows the likelihood function for the data (\(\sigma\) was set to be \(\sqrt{\text{Var}[x]/N}\)). The right panel shows the two posteriors and their MAP estimates.#

Thanks to the modern computer, making both ML and MAP estimates can be as simple as finding the maximum value of a curve. What is nice then about using a Bayesian framework here is that we are explicitly incorporating any priors that we want and we don’t need to do too much theoretical work. Moreover, we bring up the Bayesian method because it more naturally facilitates talking about the whole distribution instead of a single point estimate. In fact, because the point of a Bayesian analysis is to end up with a distributional description, researchers often use the posterior expected value or posterior median as their point estimate. The posterior median is often preferred since it is less sensitive to outliers or bad priors, as can be seen in Fig. 17, where a bad prior caused the posterior to be multi-modal (have multiple peaks).

We also bring up the Bayesian approach because it makes clear some of the implicit assumptions that often accompany an MLE. For example, the likelihood function and a uniform prior gives a posterior that is identical to the likelihood, so that the MLE and MAP estimate will be the same. This can clearly be seen in the blue lines in Fig. 16, where the likelihood and posterior functions are both normal distributions that are centered on our MLE \(\hat{\mu} = \bar{x}\). In this way, the Bayesian approach is somewhat more flexible than the MLE approach in that we can loosen some assumptions on the parameters.

Fig. 17 Illustration of the MAP estimation of the mean of \(N=100\) normally distributed random variables under two different priors as in Fig. 16.#

In any case, hopefully you now have some idea of the choices we can make when giving our collaborator just one number to describe parameters. When we have some theory about how a parameter is distributed, we can try to make an MLE. If we have a prior model for the parameter and a likelihood model for the data, then we can make posterior-based estimates.

MAP estimates

MAP estimation is similar to ML estimation in that it is dependent on some theory in order to work. However, incorporating priors can allow for greater flexibility in assumptions.

For a more detailed example of how to make a MAP estimate of quantities derived from exponentially distributed data (for example, from the time intervals from the bacterial chemotaxis data), look to the end of the notes. You will use the code and results of that example in Assignment 2!

Try It Yourself!

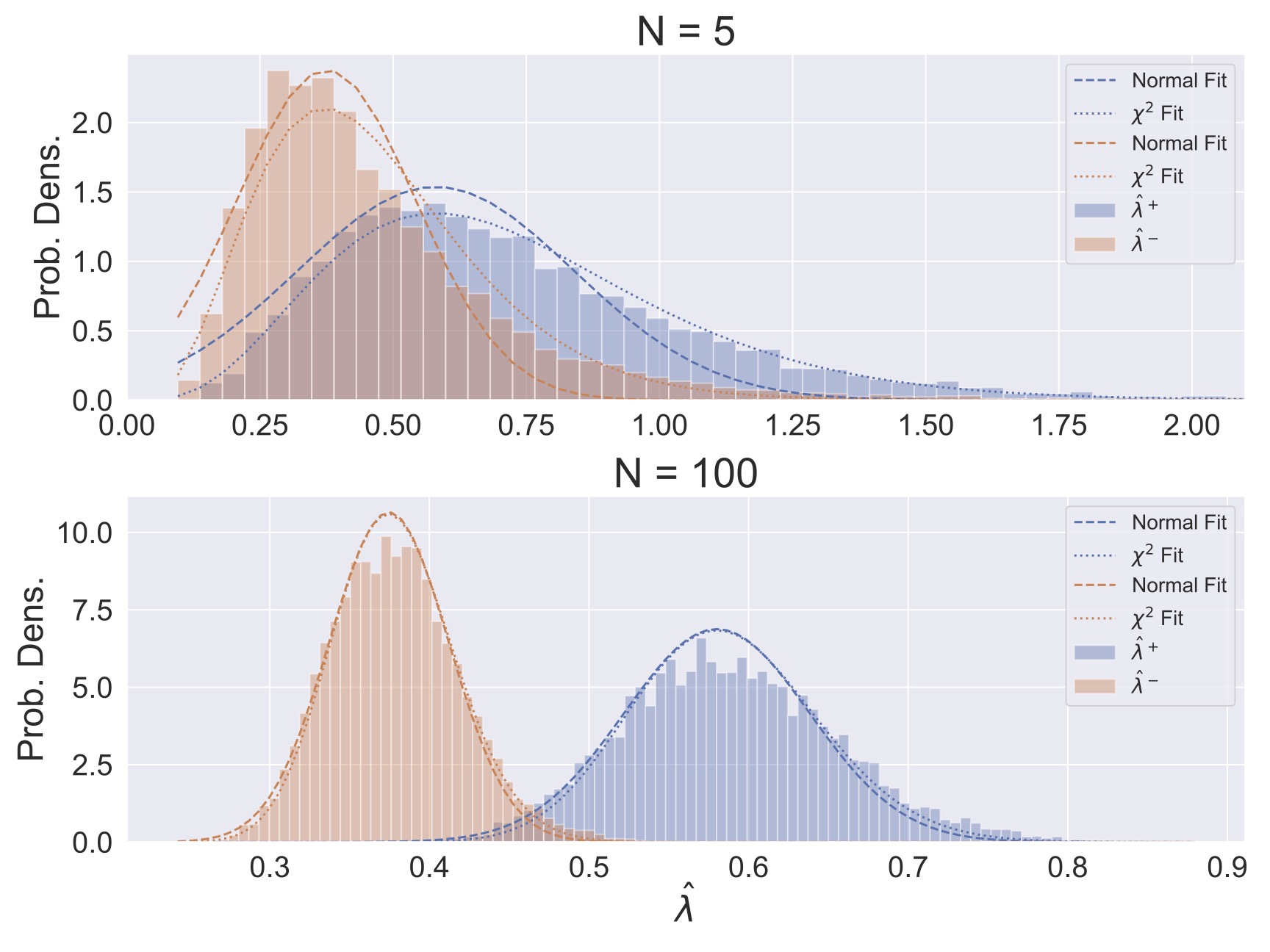

Use your Assignment 1 solutions or those provided to generate a MAP estimate of the switching rate \(\lambda^+\) or \(\lambda^-\) by maximizing the posterior distributions computationally. That is, implement a solution and find the value of \(\lambda\) at which the posterior is maximized. Compare this value to the posterior mean, median, and the MLE.

Intervals of confidence#

If you’re following closely, you may have noted that the previous section, while elaborating on topics from the first chapter, still didn’t answer all of our questions:

How likely am I to observe this estimate?

How confident are you in this estimate?

How much deviation from this estimate should I expect?

This is intentional; it helps to ground yourself more specifically in the problem at hand before we introduce the nebulous quantity of confidence. Recall your earlier experiments with \(x_i\) and \(x_j\) and how you measured \(\bar{x}\) to be 9, 10, and 12, depending on which data was included in the calculation. We also discussed how depending on what type of estimator you decide to calculate, you might report different numbers. So the path forward might still seem a bit murky.

One potential solution is to model the sample distribution for the parameter (say, \(\hat{\mu}\)) and report that the MLE = \(\bar{x}= 10\) has a likelihood of 0.12, so that we can answer our first question. But turning to the second, that answer might be concerning: 88% of the time it is not that number! How can that be our report? How can we have confidence in something that only happens 12% of the time?

The answer, as you have probably started to pick up on, is to use the probabilistic and distributional nature of these quantities to look not just at single points, but also to look at probabilities of whole regions of parameter space. That is, rather than saying “\(\hat{\mu} = 10\)”, we’d like to say things like, “I expect \(\hat{\theta}\) to be in this interval 82% of the time” or “60% of new experiments will deviate from \(\hat{\theta}\) by 2 or less.” In particular, this section will work on the development of specific types of intervals: confidence intervals, credible intervals, and finally, the use of bootstrapping to generate confidence intervals.

Before we get too much further, it’s also worth commenting on what we mean by confidence. Intuitively, it is useful to think about the phrase “I have [insert percentage]% confidence in this parameter having these values,” so that “confidence” becomes synonymous with “probability of observation.” This is a useful intuition as it lets us quantify a desirable outcome of our analysis. However, as we’ll explain, the exact way that statement this will manifest itself will depend on how we decide to construct our intervals.

Confidence intervals#

First, and most briefly, we need to discuss confidence intervals. Most directly, confidence intervals describe a region into which the true parameter value falls into \(1-\alpha\%\) of the time. (\(\alpha\) is known as the confidence level) This is a precise and somewhat confusing statement, so it bears rephrasing: if you were to perform an experiment 100 times and measure the parameter estimate, \(\hat{\theta}\), and the 80% confidence interval of each of those experiments, then we would expect 80 of those confidence intervals to contain the true population parameter, \(\theta\). This website provides an excellent visualization of how this works.

These comments are necessary before getting into the how we calculate confidence intervals because this is a non-obvious part of these tools. Confidence intervals represent the range I would need to report to cover myself from being disagreed with in \(1-\alpha\)% of future experiments. This is a very different quantity than the confidence we’ll be assessing with credible intervals.

OK, now for the how of confidence intervals. Typically, as with ML estimation, one has to know something about how the parameter of interest is distributed, then intervals can be worked out based on that parameterization. For example, the sample mean, \(\bar{x}\) is distributed normally, so we can say that it has a confidence interval given by

where \(z_{\alpha/2}\) is the \(\alpha/2^{\text{th}}\) percentile of the standard normal (\(z\)) distribution, and \(s\) is the sample standard deviation \(\frac{1}{N-1}\sum_{i=1}^N\left(x_i-\bar{x}\right)^2\). This is because this is the region in which \(\alpha\)% of the probability of a normal distribution lies.

That is, in general, we calculate confidence intervals by determining upper and lower bounds for a region such that some fraction of a distribution’s probability falls in that region. The amount of probability that we want in the region is called the confidence level, and is typically indicated with \(1-\alpha\). Common values for \(\alpha\) are 0.1, 0.05, or 0.01 (90%, 95%, or 99%), depending on the field of research and type of data.\

Try It Yourself!

Use this formula to add on to the work you did in Worksheet 1.2. Specifically, how does the confidence interval change as you change \(N\), \(M\), and \(p\)?

More formally, if we have a parameter, \(\theta\), then we want to solve

for \(L\) and \(U\), our lower and upper bounds. Equation (18) is the result of solving this for the case when \(\theta = \mu\), the mean of a set of random variables, so that \(P(\theta)\) is a normal distribution. But for other parameters that are distributed differently, like a Poisson rate parameter or a regression coefficient, we’ll need to solve this anew. It often works to approximate the confidence interval with (18), which is likely why it seems intuitive to use mean\(\pm\)standard deviation as a confidence interval of sorts, but it doesn’t work frequently or generally enough to be our only tool. At the end of these notes we’ll delve into the derivation of the confidence interval for an exponentially rate parameter that you will make use of in the assignment.

Indeed, it is precisely because of this specificity that we move on to other methods. It is not to say that knowing about confidence intervals is not useful, just that keeping a list of theoretical derivations is not generically useful enough to be the only weapon in your arsenal.

Credible intervals#

An alternative approach is the Bayesian credible interval, which is an interval of “confidence” that we can generate from a posterior distribution. Specifically, if we have a posterior distribution for how our parameter of interest, \(\theta\), is distributed, then we can use the usual interpretation of a probability distribution to find bounds around \(\hat{\theta}\), our estimate, the enclose \(1-\alpha\)% of the probability (mass) of \(\theta\) occurring. That is, rather than worrying about exactly how \(\theta\) is distributed theoretically, we can consider our posterior and find a region that contains 95% of the probability (if \(\alpha = 0.05\)).

To do this, we have a few options, but we’ll only discuss the easiest: calculate the CDF and find the \(\alpha/2^{\text{th}}\) and \((1-\alpha/2)^{\text{th}}\) percentiles.

The interval between these two points is a region in which \(\theta\) has a likelihood of \((1-\alpha)\)% of existing.

Note that the use of this interval is slightly different than that of a confidence interval in that we are directly considering \(\theta\) to be a random variable and we are discussing the probability of \(\theta\) existing in a certain region. Confidence intervals estimated our ability to know the true value of \(\theta\), which is not a random variable, and therefore are useful in the context of setting expectations for further experimentation. The credible interval describes our confidence right now about where \(theta\) lies.

Again, when we use a uniform prior on our parameter \(\theta\), then the credible interval should coincide with the confidence interval. The main benefit then of using a Bayesian approach is basically that if we’re going to be computationally generating the confidence interval anyways, then we might as well explicitly indicate what prior beliefs we have. Always assuming that the parameter is uniform is clearly not a robust or safe assessment!

Finally, we note that while taking the interval given by the \(\alpha/2^{\text{th}}\) and \((1-\alpha/2)^{\text{th}}\) percentiles gives an interval with the correct amount of probability, it is not the only interval that gives this amount of probability. For example, at a confidence level of 90%, we could have chosen the \(1^{\text{st}}\) and \(91^{\text{st}}\) percentiles, or the \(7^{\text{th}}\) and \(97^{\text{th}}\). Given this, it is sometimes recommended to find the interval containing \(1-\alpha\)% probability that is the smallest. This is called a highest density region or HDR. For most unimodal (only one peak) posteriors the HDR is very similar to the difference between the \(\alpha/2^{\text{th}}\) and \((1-\alpha/2)^{\text{th}}\) percentiles, but for multimodal distributions, the HDR might be more intuitive, as explained in this post.

In any case, the technical differences between using an HDR or percentiles are secondary to the probabilistic interpretation of the credible interval as a region where I think \(\theta\) exists now. Confidence intervals, which describe how well I think I can measure \(\theta\) in any given experiment, are a different beast.

Bootstrapping#

Given the difficulties with both of the previous methods (confidence intervals are theoretically difficult and credible intervals can be computationally difficult), you may be feeling a bit worried about how hard it is to answer “where is \(\theta\)!?” Thankfully, the modern computer has given us the ability to use a computational technique known as bootstrapping.

As described somewhat comprehensively in 1986, Tibshirani and Efron showed that if we have some data, \(x_i\) and we want to estimate some parameter \(\theta\). We can approximate the true distribution of \(\theta\) by resampling our data with replacement and recalculating \(\theta\) on our resampled datasets.

That is, I take my data \(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_N\) and I make a new data set of \(N\) points by randomly drawing data points from my collection \(x_i\), where each random draw comes from the full set of \(x_i\), so that my new data set may have multiple \(x_2\) and \(x_{17*\) (for example). This is what is meant by with replacement; if we were drawing our cards from a deck, I would be replacing the cards I had drawn so the deck is always full.

Using this new data set, I calculate \(\hat{\theta}\). Then I generate a new data set and do it again. Then I do the process again many times. Eventually I will have a distribution for \(\hat{\theta}\) and it can be shown that this distribution will eventually (with resampling) become equivalent to the sampling distribution that I was trying to describe with a confidence interval. So instead of performing a bunch of theoretical calculations, I can instead look at the percentiles of the bootstrapped distribution for \(\hat{\theta}\) to give my confidence interval, regardless of whether I know the exact way of writing down the distribution theoretically.

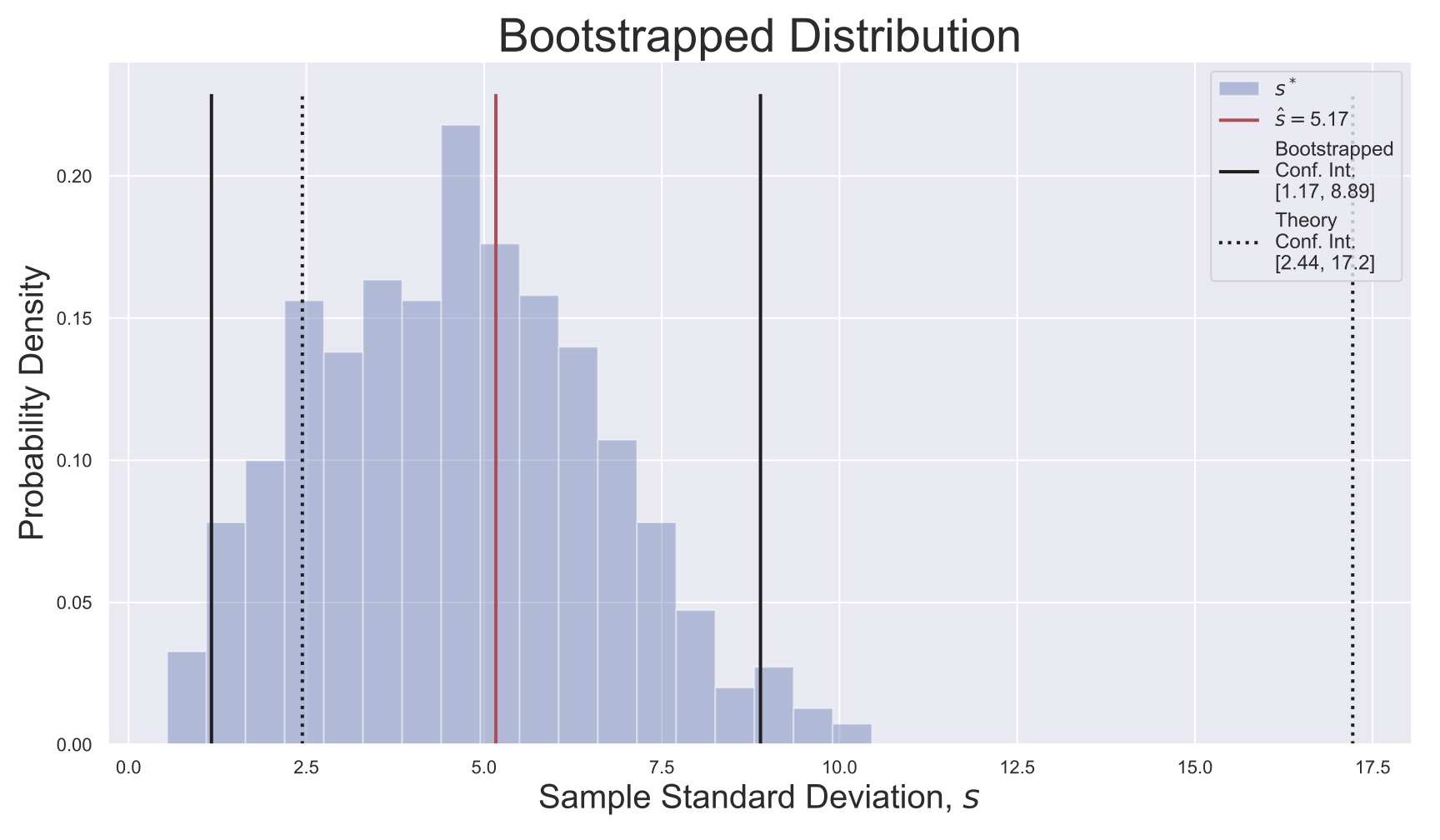

Fig. 18 Bootstrapped distribution for the sample standard deviation ((19)). The original sample’s estimate \(\hat{s}\) is shown, as are the theoretical and bootstrapped confidence intervals. Note that the theory here does not match well with the bootstrapping because the random variables \(x_i\) were actually uniformly distributed, not normally distributed, which may have been hard to assess with only \(N=10\) samples!#

To be extremely explicit, consider the following example where I have \(N=10\) observations

and I calculate their standard deviation

(The value above is actually known as the unbiased estimator for the standard deviation, but that is a detail.) I want to know the confidence interval for \(s\), but I don’t know theoretically how it’s distributed, so I’m going to use bootstrapping. (For normally distributed data, \(s\) is distributed according to the aptly named Standard Deviation Distribution.)

To do this, I generate a new list of observations by randomly picking from \(\vec{x*\). For example,

where I can get multiple of one of my initial values because each time I pick, I pick from the full list. (As a quick hack, I generated these numbers in Python using newIndices = (np.random.rand(10)*10).astype(int) + 1. See if you can make sense of this for your own use, or ask about it in class!)

Using \(\vec{x}_1^*\), I then use Equation (19) to calculate a new standard deviation \(s_1^*\). I then repeat this process \(N_{BOOT}\) times: I generate \(\vec{x}_1^*, \vec{x}_2^*, \ldots, \vec{x}_{N_{BOOT}}^*\) (we can collect these into an \(N_{BOOT}\times N\) array called \(X^*\)). And I calculate \(s_1^*, s_2^*, \ldots, s_{N_{BOOT}}^*\) and I plot their distribution. If I’m interested in an \(\alpha=5\%\) confidence level, then I can find the empirical \(2.5^{\text{th}}\) and \(97.5^{\text{th}}\) percentiles and report that 95% of the time, \(\hat{s}\) falls in that region.

Bootstrapping confidence intervals

Given \(N\) data points \(\vec{x}\), and a parameter \(\theta(\vec{x})\), we can generate confidence intervals at a confidence level \(\alpha\) with the following process:

Generate \(N_{BOOT}\) resamplings of \(\vec{x}\) with replacement: \(\vec{x}_j^*\).

Calculate \(\theta^* = \theta(\vec{x}_j^*)\) for \(j=1,\ldots,N_{BOOT}\).

The confidence interval is the \(\alpha/2^{\text{th}}\) and \((1-\alpha/2)^{\text{th}}\) percentiles of the distribution of \(\theta^*\).

Hopefully you can see that this is a relatively easy technique to use, it can be straightforwardly applied to many data sets, and its results are very interpretable, making bootstrapping an immensely useful tool.

Try It Yourself!

At this point you should have everything you need to attempt Worksheet 2.1.

Once you’ve completed that, you should be able to start on Assignment 2, Problem 1.

The atom of model fitting: least-squares regression#

At this point, hopefully you can see that we have at least attempted to answer our questions:

How likely am I to observe this estimate?

Answer: I can read off the height of the likelihood, posterior, or empirical bootstrapped distribution at that value to get this answer.

How confident are you in this estimate?

Answer: Using a confidence or credible interval, I can describe regions of confidence.

How much deviation from this estimate should I expect?

Answer: Confidence intervals give me bounds that overlap the underlying truth \((1-\alpha)\%\) of the time. Credible intervals tell me where \((1-\alpha)\%\) of the probability of observing \(\theta\) is, given my data.

Furthermore, we now have the tools to really get into something interesting: model fitting.

In science, we are generically trying to build relationships between different phenomena. When I increase the volume of a gas, what happens to its temperature? If a neuron fires in one location of your brain, do you subsequently kick your leg? If I place a chemical gradient over some bacteria, which direction do they move? To do this, we use models, which can be extremely descriptive or very generic.

Why do we use these models? This is a somewhat deep question that many people have different answers for, but our answer is practical. The point of having a model is twofold:

A good model allows you to extrapolate beyond the regimes spanned by your measurements and to make new predictions.

A robust model that performs well in a variety of situations might be hinting at an underlying principle that can bring predictive understanding to a broader range of phenomena. \end{enumerate* Either of these reasons would be sufficient justification for using modeling as a part of the scientific method, but it is worth noting that both are powerful and useful statements.

These models usually have parameters, which are quantities that often have some physical significance, and these parameters themselves need to be measured or estimated in order for the model to make sense. This is the problem of model fitting: I think that I have the correct functional shape for my relationship (my quantities are related linearly, or logarithmically, or some other way), and I want to use my data to estimate the parameters of the model. In this way, you can see why we first talked about parameter estimation: model fitting is a specific application of this concept!

Ordinary least-squares regression#

In the following section we will present the method of ordinary least-squares (OLS) linear regression. This may seem to some readers to be a trivially simple method, but we hope that our discussion serves as a useful guide to ideas that generalize to more advanced methods that you might encounter. In this way, we’ll be using linear regression as an example on which we can explore the concepts of model-fitting capability, under- and over-fitting, and predictive ability.

There are many ways to go about model fitting, but one of the most robust, famous, useful, and simplest methods is the method of least-squares regression. In the simplest version of this method, we have \(N\) pairs of data points \((x_i, y_i)\) and we want to build a relationship between them. For this example, call \(x\) the independent variable and \(y\) the dependent variable; that is, we’re going to model \(y\) as depending on \(x\). In the context of regression, we often call \(x\) the covariates and \(y\) the response. Let’s then pose the model \(f(\vec{x}, \Theta)\), where \(\Theta\) are the parameters of the model. We don’t expect our model to be immediately (or really, ever) perfect, so let’s define the residual to be discrepancy between the model and the data:

The method of least-squares then seeks to find the values of the parameters \(\Theta\) that minimize the sum of the squared residuals:

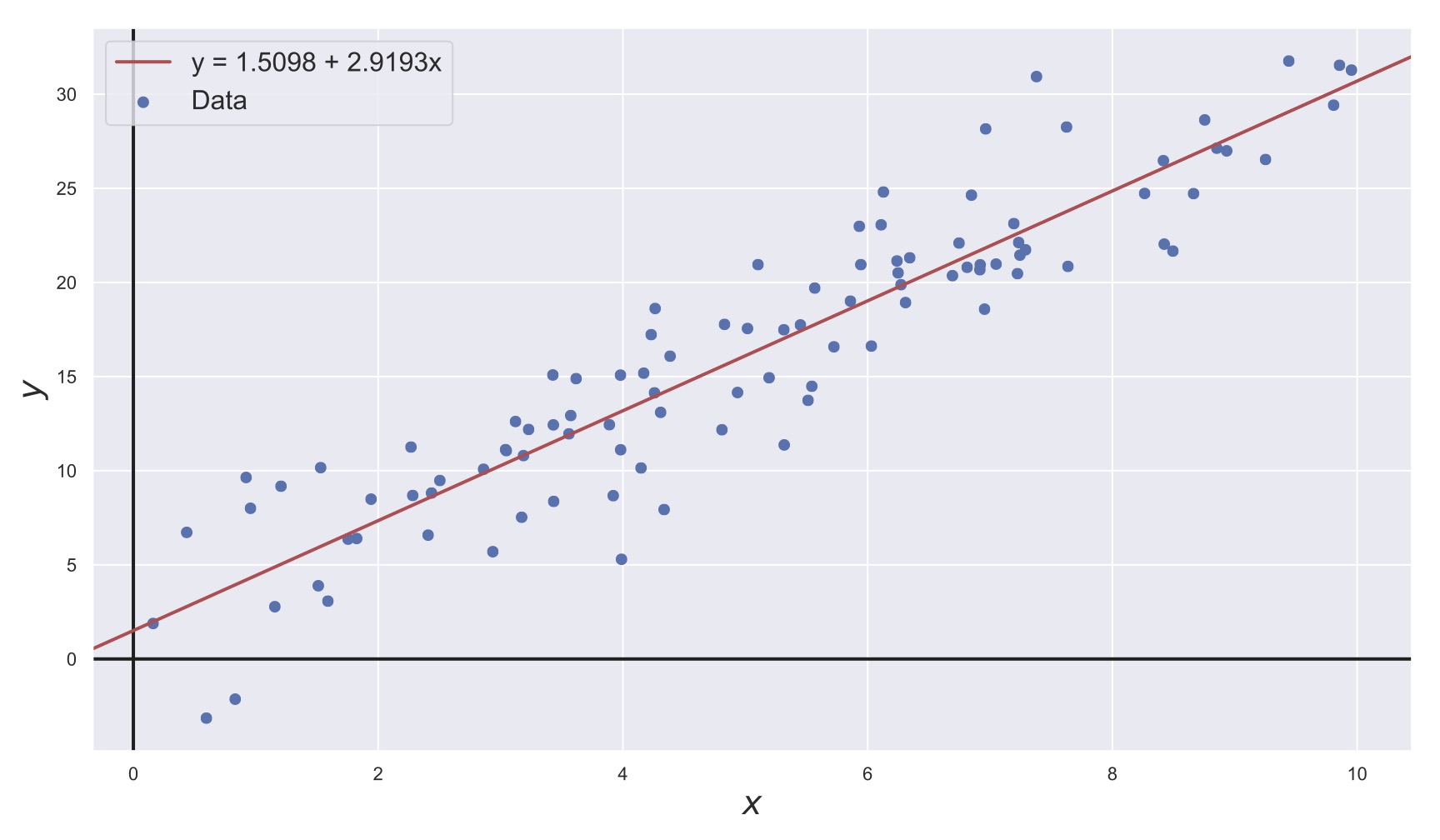

This may seem somewhat technical, but it can also be observed graphically. Consider Fig. 19. In this figure, we have data points \((x_i, y_i)\) and we want to fit a line through this data. The method of least-squares considers the vertical deviations of the line from each \(y_i\) (the residual) and tries to minimize them.

Fig. 19 Least-squares fit of a linear model, shown in red. The data to which the model is fit are shown in blue.#

That is, the method of least-squares suggests that the “best” line through the data is the one that generates the smallest average (squared) residual for any given data point.

It is worth noting that this is not the only way that we could have defined “best.” We could have used the absolute value of the residuals, we could use a weighted sum of the squared residuals because we want the line to fit certain data points better than others, we could redefine the residual to be a different distance. There are endless choices, and indeed many of these other choices have been explored by statisticians and scientists. The thought here is not that you need to always consider the entire spectrum of choices (obviously not, since most people don’t consider anything other than OLS), but just to point out that this is a choice that you as an analyzer can make. One of the goals of this course overall is that regardless of how you make this choice, you will be able to assess your confidence in the outcome, and based on that you can make different choices.

That being said, there are some good reasons to use this method. First, the democracy with which the data points are treated is the best way to examine new data set. That is, I don’t know a priori which data points are more or less important to my model, so I should treat them all the same as in OLS.

There is also a practical reason for using least-squares. The mathematical and computational algorithm for calculating the best-fit parameters is incredibly straightforward and fast. Before computers this mattered a lot, and even now, it makes more expensive techniques like bootstrapping and Markov Chain simulation that much more tractable if they can use fast algorithms many times.

The final reason is historical. Most advanced techniques in model fitting are based on modifications to least-squares. In order to understand more complex methods, understanding the strengths and weaknesses of ordinary least-squares (OLS) is a prerequisite.

Maximum-likelihood formulation#

So how then do we actually solve this problem? In this subsection we’ll outline the math of the OLS solution for linear regression. Later we’ll talk about non-linear models, but it is instructive to consider the linear case first.

As a reader, you should not worry about following all of the math perfectly, but should try and establish some intuition about the results.

Lets start with the simple scenario where we have data about a single response variable and a single covariate. The classical way is to postulate the following:

That is, \(y\) depends on \(x\) linearly plus some noise, \(\varepsilon\) that is normally distributed with mean \(=0\) and variance \(\sigma^2\).

This lets us think about \(y_i\) as a random variable with a mean that depends on \(x_i\) linearly. Specifically:

so that we can write the likelihood of observing any given \(y_i\)

Assuming then that each \((x_i, y_i)\) pair is independent, the likelihood of observing all of \(\vec{y} = [y_1,y_2,\ldots, y_N]\) can be written as the product of the individual likelihoods.

Since \(\frac{\sum_{i=1}^Nr_i^2}{2\sigma^2}\) is always positive, you can see then that maximizing the likelihood is equivalent to minimizing the sum of squared residuals! We wrote this in the context of a linear model, but it’s worth noting that this is true for any model \(y_i = f(x_i, \beta)\).

OLS maximizes likelihood

The solution to an ordinary least-squares problem is equivalent to finding the maximum likelihood estimator. (Assuming that the noise is Gaussian distributed.)

We’ve emphasized this in the text above, but we want to point out that many classical results in probability, statistics, and machine learning are predicated on some of the variables being normally distributed. While this is not a terrible assumption in the grand scheme of things, it does present difficulties when you aren’t sure that your problem fits these assumptions. The reason that we don’t stop the text here and tell you to use boilerplate algorithms is because there are other useful ways to make probabilistic statements about that data without resting on these assumptions. In any case, for the purposes of concreteness, we’re going to see where the Gaussian approach can take us for a while longer.

Continuing on, just as we did in the section on ML estimation, we can use calculus to find the maximum of Equation (21) with respect to \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\), our regression coefficients. Again, don’t worry if you can’t parse the algebra and notation, the takeaway here is that we can turn the crank of ML estimation to get formulas for the \(\beta\) that maximize the likelihood (minimize the sum of squared residuals), given our assumptions about the noise being Gaussian.

In the case of our single covariate linear regression (Equation (20)), we can derive the following:

where the \(\sum\) is notation that indicates a sum over terms that iterate \(i=1,\ldots,N\). (\(\sum x_i = x_1 + x_2 + \cdots + x_N\)).

This may seem complicated, but we can streamline this using linear algebra and matrix notation to write

where

Computers are very good at matrix operations, so this computation is very fast. Notice also that this notation allows us to generalize to as many covariates as we’d like by adding more columns to \(X\) and more rows to \(\vec{\beta}\).

OLS Linear Regression

The solution to the least-squares problem for a linear model can be found with the formula:

To understand this formula more concretely, consider the example at the end of these notes.

Try It Yourself!

At this point, you should be able to attempt Worksheet 2.2.

Once you’ve finished that, you should be able to start the rest of Assignment 2.

Residual Distributions#

You may have noticed a potentially large assumption in the previous subsection: the likelihood function depended on the fact that the noise, \(\varepsilon_i\), was Gaussian-distributed with a constant variance \(\sigma^2\). It turns out the that the OLS solution in Equation (23) doesn’t depend on this assumption of Gaussianity, but the interpretation of the estimate as a maximum likelihood estimator, does. Furthermore, and more importantly, the theoretical derivation of the confidence intervals for our estimates \(\hat{\beta}\) will depend on this assumption. As you’ll see, this makes a tool such as bootstrapping even more useful, as it will generate confidence intervals regardless of the underlying noise distribution.

Besides assuming that the noise is normally-distributed, the OLS solution also depends on the assumption that the variance in the residuals is constant, which is known as homoscedasticity. Mathematically, this appears in the fact that the size of the noise, \(\sigma^2\), in our posing of the problem (Equation (20)) is constant and doesn’t depend on \(x_i\) (otherwise we might have said \(\epsilon_i = \mathcal{N}\left(0, \sigma_i^2\right)\)). But what this means in real terms is that we’re assuming the noise is the same over the whole range of our measurements.

For example, imagine that you are measuring the relationship between temperature and humidity in the atmosphere and you have one thermometer that is very good when the temperature is above freezing, but doesn’t work otherwise, and you have another thermometer for when it’s below freezing. Na”ively you would expect that these two devices would have different measurement errors, and even that their measurement errors change as you approach the edge of their measurement range, but if you didn’t indicate this in your analysis, OLS would treat their data as being equivalently errorful.

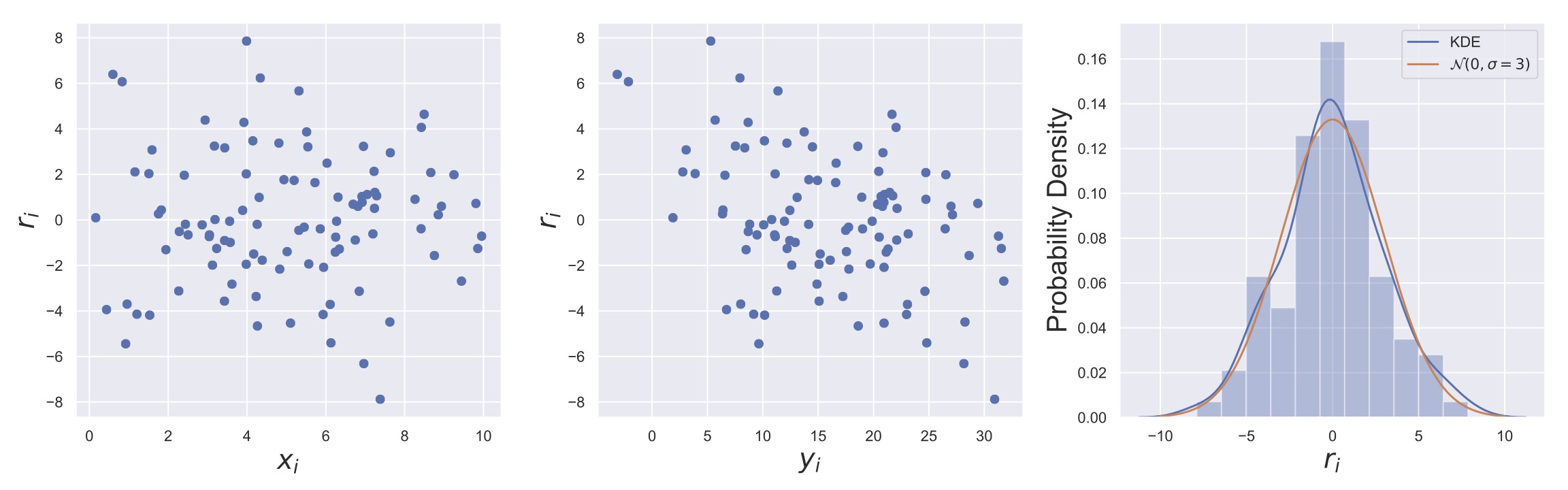

As a result, it is generically prudent to examine the residual plot, that is, \(r_i\) as a function of \(x_i\) (and sometimes as a function of \(y_i\)!). Also, you should consider the distribution of \(r_i\) to ensure that it is at least somewhat normally-distributed (although we haven’t yet talked about how to verify this quantitatively). Again OLS doesn’t assume Gaussianity but the MLEs of the \(\beta\)’s do. So if you are using the MLE solution to OLS then checking the assumptions of the two approaches seems wise! It is this philosophy that we wish to convey throughout this course: running modern machine-learning and statistical algorithms on your computers isn’t hard. What is hard, and rarely done, are directed explorations of whether the approaches are valid and what your confidence in the results is.

Fig. 20 Three different ways of examining the residuals of an OLS linear regression fit. The left panel shows how \(r_i\) depends on \(x_i\), if there were a violation of homoscedasticity, it would show up here as a relationship between \(r_i\) and \(x_i\). The center plot shows \(r_i\) vs \(y_i\). The downward trend in the residuals suggests that the model is overshooting the data when the response is small (large positive residual) and undershooting when the response is large (large negative residual). The right plot shows the distribution of residuals along side a normal distribution with zero mean and \(\sigma = 3\), which is the value that was used to generate the data.#

As an example of such diagnostic plots, consider Fig. 20. These plots can be immensely useful in determining whether there are any biases in your fits or any violations of the OLS assumptions. Also potentially useful is Seaborn’s residplot, which plots \(r_i\) vs \(x_i\) with a special kind of smoothing line over the top, as shown here. For now, we leave this recommendation as a qualitative assessment that you can perform after fitting your model, but in the next sections, we’ll establish how you can make this assessment quantitative. Finally, note that all fitting routines will generate residuals, so you can always make these figures and assess the appropriateness of the fitting assumptions.

Try It Yourself!

Using your data and model from Worksheet 2.2, recreate Fig. 20. Discuss any patterns that you observe.

Maximum a posteriori formulation#

We can also pose the problem of estimating \(\beta\) in a Bayesian sense. This section is more mathematically technical, so again, try and focus on the words and results if you are uneasy about algebra and mathematical notation.

In this formulation of the problem, we will again assume that the response depends linearly on the covariates plus some Gaussian noise so that we can write the likelihood as in equation (21). However, now we will explicitly model \(\beta_0\), \(\beta_1\), and \(\sigma\) (the parameter that OLS linear regression somewhat ignores) so that we can construct a posterior distribution for each of them.

This can be done several ways, but the algebra can be facilitated by choosing a conjugate prior so that the math is easier to work with. Also, for ease of notation, we will be using \(\vec{\beta}, X,\) and \(\vec{y}\) as defined in equation (22). The likelihood function is a normal distribution for \(\vec{\beta}\), so a conjugate prior for \(\vec{\beta}\) is also normal, while the likelihood function is a gamma distribution for \(\sigma\), and so it turns out that an inverse Gamma distribution provides a conjugate prior.

It’s worth noting that you don’t need to do this to construct a posterior - we can choose any prior and make the calculation empirically - but as your problem becomes more complicated, it can help to have algebraic forms for certain things. In any case, if you want to skip the rest of this derivation and use the result, that’s definitely acceptable, this reference should provide a workflow for how to attack new problems.

We write the priors explicitly as:

and

Here, \(\mathcal{N}_P\) is a multivariate Gaussian distribution with

(\(\mathbb{I}_P\) is the \(P\times P\) identity matrix. In our case, \(P=2\).)

Notice then that these priors each introduce new parameters, \(\vec{\mu}_{\beta}\), \(\delta_{\beta}\), \(a_{0}\), and \(b_{0}\), however, as we know, the effect of priors quickly fades with the addition of data, so the exact values of these parameters isn’t that important. However, if we do have some information about \(\vec{\beta}\) or \(\sigma\), this method allows us to incorporate this information by design.

When using the Bayesian linear regression, it is often recommended to use \(\vec{\mu}_{\beta} = \vec{\beta}_{OLS}\), the result from equation (23), and \(\delta_{\beta}\) large (center the prior distribution on the OLS solution but give it a large spread to allow for variation). Similarly, a flat (uninformed) prior for \(\sigma\) can be set by using \(a_{0} = b_{0} = 0.001\) (or some other small number, verify this yourself!).

It’s also worth noting that we have set the prior for \(\vec{\beta}\) as a conditional distribution on our other parameter \(\sigma\). This is intentional, but not necessary in general for other problems, but does give the posterior some nice properties in this case that are not worth discussing here. You can see that Bayes Theorem is flexible enough to allow this when we write

where \(P\left(\vec{\beta}, \sigma\right)\) is the joint distribution for \(\vec{\beta}\) and \(\sigma\), and our properties of probability distributions tell us that \(P(A, B) = P(A|B)P(B) = P(B|A)P(A)\) so that we can use \(P\left(\vec{\beta}, \sigma\right) = P\left(\left.\vec{\beta}\right|\sigma\right)P(\sigma)\) as our prior.

Finally then, we can multiply these distributions and normalize to find the joint distribution \(P\left(\vec{\beta}, \sigma\right)\). This will initially look like a big mess, but we’re only interested in posteriors for just \(\vec{\beta}\) or just \(\sigma\), so we can marginalize (sum over \(\sigma\) to get \(P\left(\vec{\beta}|\cdots\right)\) or sum over \(\vec{\beta}\) to get \(P(\sigma|\cdots)\) to get the following:

where

The posterior for \(\sigma\) becomes

where

We can then find the maxima of these posteriors, or their moments, or their percentiles, etc. We can also draw samples from these distributions to empirically find moments, credible intervals, etc. if we don’t want to do any more theory!

Finally, it’s worth noting that when \(\delta_{\beta}\) is large, then \(\vec{\eta}_{\beta} \rightarrow (X^TX)^{-1}X^T\vec{y}\), the OLS solution. Also, the mean of an inverse gamma distribution is given by \(b/(a-1)\), so again if \(\delta_{\beta}\) is large and \(a_{0}\) and \(b_{0}\) are small, then the mean becomes

which is the OLS point estimator for the variance.

This work may have seemed very technical, and it was. We omitted a ton of algebra that can be shared upon request (a later version of these notes will put the details somewhere), but the point remains that we can also solve this problem using a Bayesian framework. Furthermore, this framework explicitly allows for the incorporation of previous knowledge and directly gives us distributional descriptions of our quantities of interest. Although we won’t discuss it here, the Bayesian methods can relatively straightforwardly be adapted to account for heteroscedasticity, different models for the noise, or other more complicated variable dependencies. Given this flexibility, the algebra can seem somewhat worth the effort!

Try It Yourself!

Following the example at the end of the notes, implement Bayesian OLS Linear Regression to your data from Worksheet 2.2. How do the distributions for the regression coefficients and noise spread (\(\sigma\)) compare to the values you used to make the data?

Confidence regions for model parameters#

We’ve now discussed how to make point estimates of regression coefficients by maximizing the likelihood of the data and by considering posterior distributions of \(\vec{\beta}\), but we haven’t finished the estimation until we’ve generated confidence regions.

You might not be surprised to learn that we’re going to discuss three approaches to determining regions of confidence in your estimates: ML estimation, examining posteriors with Bayes’ Theorem, and bootstrapping. You also won’t be surprised to see that ML estimation will involve a lot of formulas and math, often relying on assumptions of homoscedasticity and normality of the residuals. We will present those calculations below. However, as is a theme that repeats itself throughout this course, the bootstrapping approach to producing estimates for parameter bounds is comparatively practical, straightforward, and generic.

The Bayesian approach requires no additional work beyond what you have already done to make the (MAP) estimate. The whole point of the Bayesian approach is that it gives a distributional estimate of parameters, and hence you need only report some statistic or region related to the spread of the parameter in question.

In this section, we’ll just show an example of the different methods. As discussed earlier, the MLE confidence interval will be a formula that can be derived theoretically, the MAP estimator most naturally receives a credible interval that can be generated from the posterior, and we can bootstrap our OLS estimate to approximate the population distributions for our parameters and get confidence intervals computationally.

That is, we’ll explain the details of the MLE confidence interval, but the credible interval and bootstrap confidence intervals can be generated using the methods given earlier. We’ll show more detailed work and code for these methods at the end of the notes.

Confidence intervals of ML estimates of regression coefficients#

The formula for the confidence interval for a regression coefficient is

where

is the standard error in the \(j^{\text{th}}\) regression coefficient. \(t_{p, \nu}\) is the \(p^{\text{th}}\) percentile of the Student’s \(t\) distribution with \(\nu\) degrees of freedom (scipy.stats.t.ppf(p, nu)). This is a result of the fact that regression coefficients (under OLS assumptions) are \(t\)-distributed, which is probably not obvious to you. It’s worth noting that ML confidence intervals are often written as Estimate \(\pm\) Percentile \(\times\) Standard Error, but you shouldn’t assume this form unless you know that you can. In the case of regression coefficients, the standard error, is given by the formula above for \(\hat{s}_{\beta_j}\).

More generically, it can be shown that the variance in \(\beta_j\) is given by \(\Sigma_{j,j}\) (the \(j^{\text{th}}\) diagonal element of \(\Sigma\), where

This matrix is called the covariance matrix for \(\vec{\beta}\) and is relatively easy to compute (it’s often returned by your linear regression function). So once you have this matrix, you can take the square root of the \(j^{\text{th}}\) diagonal to get the standard error in that coefficient. Then the confidence interval can be found by taking \(t_{1-\alpha/2, N-2}\) plus/minus the OLS estimate \(\hat{\beta}_j\).

For a non-linear model, this formula provides an approximation to the confidence interval, but without knowing more precisely how our parameters are distributed, we cannot derive more precise intervals generically. In this case, as stated above, you may want to turn to bootstrapping as it provides an empirical route to estimating the spread in parameter estimates.

Try It Yourself!

Take a stab at Worksheet 2.3. Once that’s done, you should now be able to attempt the first three problems of Assignment 2.

Model fitting vs prediction#

One goal then of a statistical model is that it performs well on new data and not just the data on which it was built. To this point, everything we’ve discussed is related to training the model – estimating the model parameters from the data. Parallel to the process of model fitting, we also want to assess the model’s predictive ability, in particular, its ability to predict responses on previously unobserved inputs, or generalization.

As a result of these dual goals, it is often recommended in machine learning texts that you should split your data into two sets: a testing set for assessing generalization, and a training set for fitting the model (estimating the model parameters). You might see right away then that there are two errors that we want to monitor: the error in matching the training data and the error in predicting the test data. We’ll refer to these as the training and testing error, respectively.

Obviously, a very good model will have both small training and testing errors, but this is not always realized with actual data. Instead we can note that the average training error will be smaller than the average testing error, so the performance of a model can be assessed both in its ability to shrink its training error and its ability to reduce the gap between the testing and training error.

More intuitively, these two errors directly correspond to the problems of overfitting and underfitting. Underfitting results when the model is unable to to describe even the training data set. This often corresponds to a model that doesn’t have enough flexibility (or is simply inappropriate) to fit the data. As an example, think about using a linear function to fit a sinusoid. Overfitting on the other hand results from data that has incorporated the shape of the training data too much and can’t predict new data. This often corresponds to a model having too much flexibility, so that it is inferring more from the data than may be justified.

In this way, we can control whether a model is likely to over- or under-fit by altering its “capacity” or “flexibility”. Defining this quantity formally is difficult, but you can think of it as a model’s ability to fit a wide variety of functions. For example, if we extend our linear model to include a quadratic term:

it has more capacity than the linear model in Equation (20). We could then use OLS to find \(\beta_2\) in addition to the other regression coefficients and fit nonlinear models. As such, we say that models with low capacity may struggle to fit even the training set, while high capacity models might become too conformed to the training set by assuming it has features that it does not.

An appropriate, but useless, statement is that a statistical model will generally perform best when its capacity is appropriate for the true complexity of the task and the amount of training data. This topic of capacity will come back when we address regularization-based approaches to statistical modeling in Module 4. Surprising as it may seem, these approaches will attempt to modulate model capacity and fit the model in a way that is more consistent with the data.

Try It Yourself!

Split your data from Worksheet 2.2 into a testing and training set. Use the training set to fit the linear model and assess the prediction error, the discrepancy between the model prediction and the actual test data. Now swap the roles of the two sets, what can you say about your model’s generalizability?

Let’s get back to practicalities. You have a dataset and you want to train your model and assess its generalizabilty. If you have enough data, you split it into training and test sets so that you can monitor performance and fitting at the same time.

How do you know that you have enough data to do this? Empirically, we would say that such a data is large enough that we’ve reached a regime where bootstrapped estimates are insensitive to adding more data. That is, you could run the tests that you’ve been doing in the worksheets where you ramp up the number of samples that you include in your estimates. If your estimates keep changing significantly (whatever that may mean) when you add more data, then you don’t have enough data to split into two sets.

For the sake of argument, let’s say that you do have “enough” data to split into two sets (if you don’t you will just have to proceed with even more caution). How then, should you split your data? Ideally, the testing and training sets are drawn from a single common distribution, so you can na”ively guess that breaking your data along the lines of \(x < x_0\) and \(x > x_0\) will be dangerous, because there might be real differences in your data between those two sets. In such a case, not only might your training error be large because you don’t have a wide-enough range of data to fit your model, your testing error will also be large because the model will never have seen data from the other region. Instead, the best we can usually do is to select our sets randomly from our full data set. One way to do this quickly in Python is to use np.random.shuffle(np.arange(N)) to generate a shuffled list of indices. Then you can, for example, take the first 10% of these indices to grab your testing set data.

While this previous point may have been somewhat obvious, it’s a bit less obvious what proportions we should split the data. If we allocate too much data to the testing set, then we’ll get a bad fit, but if we allocate too little, then it won’t be clear whether the predictive performance was due to the data in the testing set or the model. This is especially tricky if we’re comparing two methods or models! How then can we balance this? The answer is called cross-validation, which we’ll now describe.

Try It Yourself!

Modulate the size and characteristics of your testing and training sets. How do training and testing error change as you change the size of the testing set? What happens if you break your data into two sets by putting a threshold on your covariate so that all the data below the threshold is training data and the data above is testing data? Why is this a bad idea?

Cross-Validation#

As we explained earlier, least-squares is just one of many ways that we could choose to optimize our model’s parameters. In least-squares, we decided that minimizing the discrepancy between our data and our model was the most important objective. This is by far the most common tack taken, but an interesting alternative to minimizing these discrepancies is to ask that our coefficients are those such that the model is most robust to new data. That is, maybe we’re less concerned that the model match the current data really well, and instead that it should match new future data well.

Alternately, when the parameter of interest is not a model parameter, but an analysis or algorithmic parameter, this perspective can be useful. Such parameters are called hyperparameters and are common in many machine learning or analysis algorithms.

But how can we perform such a fitting? We don’t have new data, we only have the data we’ve collected! The most common way around this is to use the technique of cross-validation (CV). This method builds on the concept of testing and training data partitions in such a way that addresses some of our questions from earlier.

In particular, cross-validation will address the concerns that our test or training sets contain outliers or the data are not evenly distributed between the sets along some covariates by going one step further than simply breaking the data into two sets. Cross-validation says that we should repeatedly break the data into two sets, each time containing different partitions of the data, and assess the accuracy across these repeated partitions. (You can think of this as bootstrapping the accuracy assessment!)

There are of course many ways to partition your data, but the most common are called \(k\)-Fold Cross-Validation and Leave One Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV). In \(k\)-fold CV, one breaks the data set into \(k\) equal sized partitions (folds) and sequentially uses each partition as the test set while using the \(k-1\) other partitions as the training set. Often \(k=10\) or \(k=5\) is used. The extreme case when \(k=N\), the size of the data set, is LOOCV. This is because we are using all of the data except one point (leaving one out!) and trying to predict that one point. There are reasons to use or not use LOOCV, but generally, the biggest concern will be how long it takes for the code to run.

The idea then is that you can use CV to fit a model by performing CV repeatedly as you change model parameters. So if I am performing regression, I can search the \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\) space to find where some prediction accuracy (the sum of squared residuals or maximum absolute residual, for example) is maximized. Alternately, if you have data that you know belong in different groups and are trying to generate a model to predict what group a data point is in, then counting the number of correct predictions can be useful.

We’ll discuss cross-validation again later when we talk about model selection, not just fitting, but we introduce it here because it is a form of parameter estimation. It’s worth noting that CV does not naturally give intervals of confidence, but you could construct a meaningful range on where you think parameters should be set by considering your accuracy vs. parameter curves.

Try It Yourself!

Apply 10-fold cross-validation to your data from Worksheet 2.2. For each fold, use bootstrapping to estimate the regression coefficients (point estimate and confidence interval). Do these distributions overlap significantly from fold to fold?

Real data! A thermodynamic model of gene regulation#

For the assignment that accompanies this text, there is a data set, which is a part of the data used in this paper by Garcia and Phillips. In this paper, Garcia and Phillips generated a thermodynamic model of a famous gene regulatory network: the network around the lac operon. This model was exceptional for a few reasons, but among the most interesting applications was that the model could be used to estimate some quantities that are generally very hard to measure: the actual number of certain proteins in a given cell and the binding energies of certain proteins to DNA.

To understand why this is interesting and how they made and fit their model, we’ll give a little background on gene regulatory networks, the lac operon specifically, and thermodynamical models. Then we’ll discuss the data and how they used it in the paper.

What is a gene regulatory network?#

The “Central Dogma of Biology” is a framework for how information is propagated from DNA to proteins. The general principle is that DNA is transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA), and then that RNA is translated into proteins. It’s shown as a cartoon in Fig. 21.

Of course, reality is not so neat, and there are actually arrows between each of the three components (DNA, RNA, and proteins) in every possible direction. That is, not only can RNA molecules generate proteins via translation, but they can also interact with DNA to affect transcription. Similarly, proteins don’t just run off to never come back to the nucleus of the cell, they often directly regulate transcription and translation, both of their own encoding genes as well as many others! As a result, biologists refer to the set of interacting DNA, RNA, and proteins as a genetic regulatory network (GRN). This name more aptly describes the biology in which a network of agents regulate the expression of one or more genes.

.](../../_images/CentralDogmaImage_Adjusted.png)

Fig. 21 Illustration of the “Central Dogma of Biology,” showing as a cartoon with arrows how DNA is transcribed into mRNA, which is then translated into proteins. Image courtesy of Khan Academy.#

The lac GRN refers then to the set of proteins and chemicals that regulate the set of genes known as the lac operon. The lac operon, as shown in Fig. 22, is a stretch of DNA in E. coli that consists of a promoter binding site, an RNA polymerase (RNAP) binding site, a repressor binding site called an operator, and three protein-coding regions for the genes lacZ, lacY, and lacA. Based on the growth curves studied by Jacob and Monod, it was noted that E. coli bacteria, when placed in an environment with two food sources, glucose and lactose, first consume the glucose, then the lactose. This suggested that there is some sort of environmental control over when the bacteria would manufacture the enzymes needed for processing lactose.

.](../../_images/Lac_operon.png)

Fig. 22 Diagram of the lac operon in each of its four states. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.#

This is indeed the case: the bacteria does not waste energy maintaining or creating enzymes for a food source when there is a much easier to consume resource, glucose, around. The effect becomes pronounced when only lactose is available, in which case many lac genes are expressed, or when there is a lot of glucose and no lactose, in which case almost no lac genes are transcribed.

This system has been extensively studied - it is probably one of the best understood regulatory networks we know of. It has been shown that when lactose is unavailable, a protein, known as a repressor binds to the DNA on the operator region, physically blocking RNAP, which transcribes the DNA into mRNA, from binding. Because this protein inhibits (or represses) expression, it is called a repressor. On the other hand, when there is low glucose, another protein called cAMP binds to the DNA in such a manner that it facilitates RNAP to bind and make the lac genes. As a result, cAMP is called a promoter in this context. The discovery of these proteins and their effects on transcription were very important because it was not always understood that organisms can modulate transcription in addition to translation.

As a result of the work put into understanding this network as a simple model for all GRNs, this network is often taught in biology courses as an introduction to the topic. It is likely for a similar reason that Garcia and Phillips chose it to model in their paper. The simplicity of the network also served to demonstrate the efficacy of applying thermodynamics to the analysis of GRNs, which was previously never attempted. Before fully diving into their data and analysis, we’ll quickly think for a moment about thermodynamics and what it can bring to the study of living cells.

Why thermodynamics?#

At this point it might not surprise you that thinking about things probabilistically is a profound and useful way of attacking problems. Indeed, we’ll see that physicists have been using it successfully for centuries, and that it in fact underpins the entire discipline of thermodynamics (and quantum mechanics, but that’s not relevant here), which is often called statistical mechanics. Thermodynamics is a branch of physics that attempts to codify the effects of temperature and heat into a set of principles.

One of the base ideas of thermodynamics is that while physically most things want to have a minimum energy, due to thermal fluctuations (random photons hitting atoms, molecules bouncing and jiggling), there is a non-zero likelihood that a system will have some non-minimal energy. Physicists have then shown that if you can then enumerate all the different states in which the system can exist and their energy levels, then you can predict the probability that the system will exist in any particular state.

Now, this might sound a bit ridiculous, if I have even a closed box of air, 1 meter to a side, I have on the order of \(10^{25}\) molecules in that box, so enumerating all of the different ways that those molecules can be arrayed in my box should seem rather insurmountable. More concretely, Boltzmann’s distribution exactly describes the probability of observing any given state as a function of that state:

\(Z\) is known as the partition function, and is the part of the problem that is impossible: sum all the states and their energies.

However, it is often possible to write down the energies and number of ways that a system can be in a few particular states, in which case we can talk about the relative probabilities of those states by dividing the two Boltzmann distributions so that \(Z\) cancels out. This is often incredibly useful, as Garcia and Phillips note in the development of their model. We’re not often concerned with the probability distribution across all possible states, but just across a few interesting ones. Known the relative likelihoods in such as situation is very powerful. In particular, we can see that

so that the relative probability of observing one state versus another is dependent on the difference in their energies.

If we consider our two states to be a molecule, say a protein, binding or not binding to another molecule, say DNA, then the relative likelihood of observing the molecules bound together compared to separate is directly connected to the binding energy of those molecules. In fact, this is often what we really mean when we talk about binding energies - we want to know the relative likelihood of the molecule being unbound versus bound.

In either case, this binding energy is a useful and interesting quantity to know, but is often difficult to measure directly. This is especially true in live biological systems, where getting a handle on such chemical measurements is confounded by the thousands of different processes occurring simultaneously. However, in posing a model that is explicitly based on thermodynamics, Garcia and Phillips were able to make in vivoestimates of the binding energy of the lacI repressor to DNA.

The experiment and how to analyze images#

With this introduction, you are now ready to understand the model and measurements that Garcia and Phillips made. First, the goal of the paper was twofold: show that a thermodynamic model might describe gene regulation, and then that that model could be used to make estimates of quantities that are normally very hard to measure, like in vivo protein numbers.

This first point is interesting because it’s not obvious that gene regulation should be an equilibrium process (as thermodynamics assumes), but it could be that it requires the use of energy (via ATP or something similar). Showing this model’s explanatory power was evidence of how the underlying processes work.

Then they used their model to make a variety of predictions, most significantly of the repressor binding energy, \(\Delta\varepsilon_{RD}\), and the repressor copy number, \(R\). (The \(RD\) stands for Repressor-DNA to indicate the binding of the repressor to DNA.) They used other more complicated techniques and results to verify their model fits and found very good agreement. This suggests that such a model fit and set of experiments might be useful for future measurements of those quantities.

The model#

Specifically, the model they fit is given in Equation 5 of their paper:

where the Fold Change in Expression is the change in fluorescence in the presence of repressors compared to when there are no repressors in the system. \(R\) is the number of repressor proteins, \(N_{NS} = 5\times10^6\) is the number of non-specific binding sites that the repressor could bind on the DNA that wouldn’t impact expression, and \(\beta = 1/k_BT\) is a Boltzmann factor.

The data#

The data consist of images of E. coli bacteria which have been modified so that the existence of certain proteins causes light at different wavelengths to be emitted. These images are known as fluorescence measurements, and are a common type of data in modern biological experiments. You will have access to several of these images for several mutant strains that are mentioned in the paper.

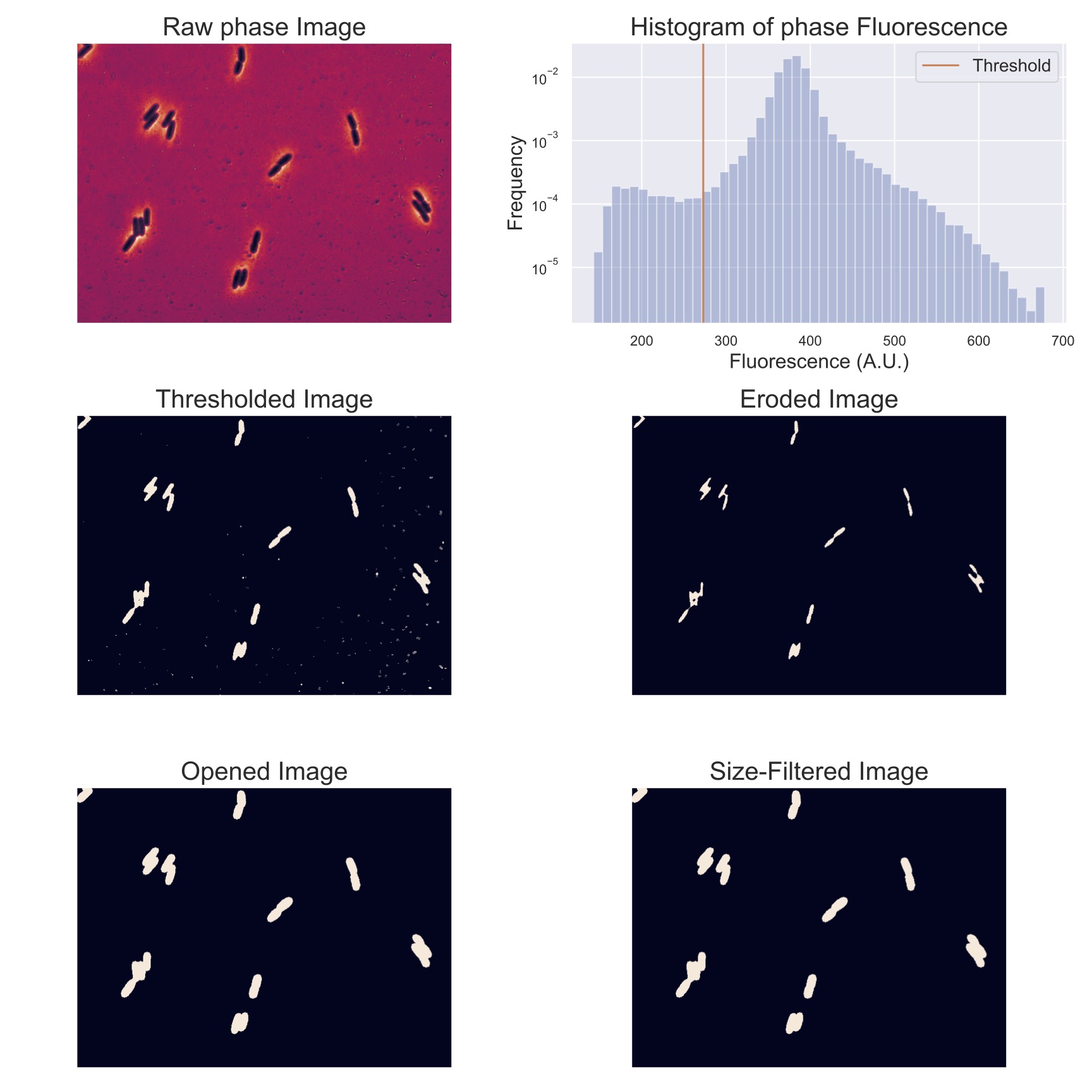

The images you have been given show the bacteria in three channels: a YFP channel, an mCherry channel, and a Phase-Contrast channel. These first two channels are named after the engineered fluorescent proteins that have been genetically inserted into the bacteria. The YFP (Yellow Fluorescent Protein) have been engineered to be attached to the lac operon, so that when those genes are expressed, the cell will fluoresce yellow. The mCherry (a red fluorescent protein) has been engineered to be expressed in all bacteria, hopefully enabling the cells to be seen compared to the background. The Phase-Contrast images are not channels corresponding to specific wavelengths, as in the previous channels, but instead look for phase shifts in the light to detect objects with different optical densities. As you can see in the images when you open them, this tends to highlight the edges of the bacteria, again potentially allowing us to extract them from the background.

Although this is not known in general, through a complicated calibration experiment, the authors were able to estimate the repressor copy number, \(R\) several strains and thus fit the model using fold-change in fluorescence as the response and \(R\) as the covariate.

Image processing#